In order to use the vertices in a GeomVertexData to render anything,

Panda needs to have a GeomPrimitive of some kind, which indexes into

the vertex table and tells Panda how to tie together the vertices to

make lines, triangles, or individual points.

There are several different kinds of GeomPrimitive objects, one for

each different kind of primitive. Each GeomPrimitive object actually

stores several different individual primitives, each of which is

represented simply as a list of vertex numbers, indexing into the

vertices stored in the associated GeomVertexData. For some

GeomPrimitive types, like GeomTriangles, all the primitives must have

a fixed number of vertex numbers (3, in the case of GeomTriangles);

for others, like GeomTristrips, each primitive can have a different

number of vertex numbers.

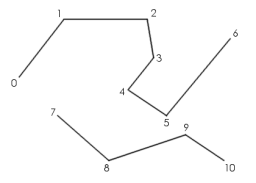

For instance, a GeomTriangles object containing three triangles, and a

GeomTristrips containing two triangle strips, might look like this:

| GeomTriangles |

|

GeomTristrips |

| 0 |

|

0 |

| 1 |

|

2 |

| 2 |

|

3 |

|

|

5 |

| 2 |

|

6 |

| 1 |

|

1 |

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

| 0 |

|

1 |

| 5 |

|

3 |

| 6 |

|

2 |

Note that the GeomPrimitive objects don't themselves contain any

vertex data; they only contain a list of vertex index numbers, which

is used to look up the actual vertex data in a GeomVertexData object,

stored elsewhere.

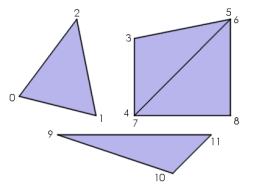

GeomTriangles

This is the most common kind of GeomPrimitive. This kind of primitive

stores any number of connected or unconnected triangles. Each

triangle must have exactly three vertices, of course. In each

triangle, the vertices should be listed in counterclockwise order, as

seen from the front of the triangle.

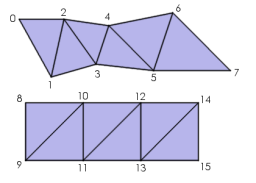

GeomTristrips

This kind of primitive stores lists of connected triangles, in a

specific arrangement called a triangle strip. You can store any

number of individual triangle strips in a single GeomTristrips object,

and each triangle strip can have an arbitrary number of vertices (at

least three).

The first three vertices of a triangle strip define one triangle, with

the vertices listed in counterclockwise order. Thereafter, each

additional vertex defines an additional triangle, based on the new

vertex and the preceding two vertices. The vertices go back and

forth, defining triangles in a zig-zag fashion.

Note that the second triangle in a triangle strip is defined in

clockwise order, the third triangle is in counterclockwise order, the

fourth triangle is in clockwise order again, and so on.

On certain hardware, particularly older SGI hardware and some console games, using triangle strips is an important

optimization to reduce the number of vertices that are sent to the

graphics pipe, since most triangles (except for the first one) can be

defined with only a single vertex, rather than three vertices for each

triangle.

Modern PC graphics cards prefer to receive a group of triangle strips connected together into one very long triangle strip, by the introduction of repeated vertices and degenerate triangles. Panda will do this automatically, but in order for this to work you should ensure that every triangle strip has an even number of vertices in it.

Furthermore, since modern PC graphics cards incorporate a short

vertex cache, they can generally render individual,

indexed triangles as fast as triangle strips; so triangle

strips are less important on PC hardware than they have been in the past. Unless you have a good reason to use a GeomTristrips, it may be easier just to use GeomTriangles.

When loading a model from an egg file, Panda will assemble the polygons into triangle strips if it can do so without making other compromises; otherwise, it will leave the polygons as individual triangles.

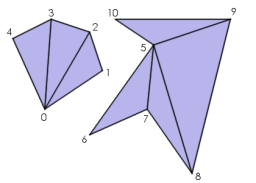

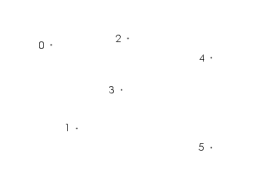

GeomTrifans

This is similar to a GeomTristrips, in that the primitive can contain

any number of triangle fans, each of which has an arbitrary number of

vertices. Within each triangle fan, the first three vertices (in

counterclockwise order) define a triangle, and each additional vertex

defines a new triangle. However, instead of using the preceding two

vertices to define each new triangle, a triangle fan uses the

previous vertex and the first vertex, which means that all of the

resulting triangles fan out from a single point, like this:

Like the triangle strip, a triangle fan can be an important

optimization on certain hardware. However, its use can actually incur

a performance penalty on modern PC hardware, because it is impossible to send more than one triangle fan in one batch, so you

probably shouldn't use triangle fans on a PC. Use GeomTriangles or GeomTristrips instead.

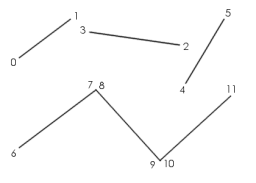

GeomLines

This kind of GeomPrimitive stores any number of connected or

unconnected line segments. It is similar to a GeomTriangles, but it

draws lines instead of triangles. Each line has exactly two vertices.

By default, line segments are one pixel wide, no matter how far away

they are from the camera. You can use

nodePath.setRenderModeThickness() to change this; if you specify a

thickness greater than 1, this will make the lines render as thick

lines, the specified number of pixels wide. However, the lines will

always be the same width in pixels, regardless of how far away from

the camera they are.

Thick lines are not supported by the DirectX

renderer; in DirectX, the thickness parameter is ignored.

GeomLinestrips

This is the analogue of a GeomTristrips object: the GeomLinestrips

object can store any number of line strips, each of which can have any

number of vertices, at least two. Within a particular line strip, the

first two vertices define a line segment; and thereafter, each new

vertex defines an additional line segment, connected end-to-end with

the previous line segment. This primitive type can be used to draw a

curve approximation with many bends fairly easily.

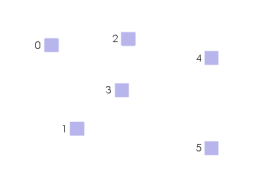

GeomPoints

This is the simplest kind of GeomPrimitive; it stores a number of

individual points. Each point has exactly one vertex.

By default, each point is rendered as one pixel. You can use

nodePath.setRenderModeThickness() to change this; if you specify a

thickness greater than 1, this will make the points render as squares

(which always face the camera), where the vertex coordinate is the

center point of the square, and the square has the specified number of

pixels along each side. Each point will always be the same width in

pixels, no matter how far it is from the camera. Unlike line

segments, thick points are supported by DirectX.

In addition to ordinary thick points, which are always the same size no matter how far they are from the camera, you can also use nodePath.setRenderModePerspective() to

enable a mode in which the points scale according to their distance

from the camera. This makes the points appear more like real objects

in the 3-D scene, and is particularly useful for rendering sprite

polygons, for instance for particle effects. In fact, Panda's

SpriteParticleRenderer takes advantage of this render mode. (This

perspective mode works only for points; it does not affect line

segments.)

Even though the sprite polygons are rendered as squares, remember they

are really defined with one vertex, and each vertex can only supply

one UV coordinate. This means each sprite normally has only one UV

coordinate pair across the whole polygon. If you want to apply a

texture to the face of each sprite, use nodePath.setTexGen() with the

mode TexGenAttrib.MPointSprite; this will generate texture coordinates

on each polygon in the range (0, 0) to (1, 1). You can then transform

the texture coordinates, if you wish, using one of the methods like

nodePath.setTexOffset(), setTexScale(), etc.

|