So far, we have only talked about ordinary 2-D texture maps.

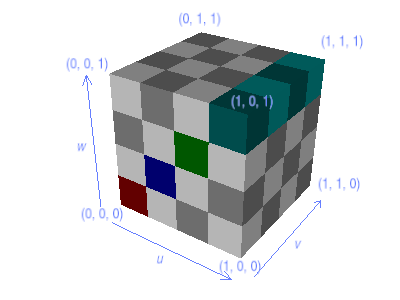

Beginning with version 1.1, Panda3D also supports the concept of a 3-D

texture map. This is a volumetric texture: in addition to a height

and a width, it also has a depth:

The 3-D texture image is solid all the way through; if we were to cut

away part of the cube we would discover that the checkerboard pattern

continues within:

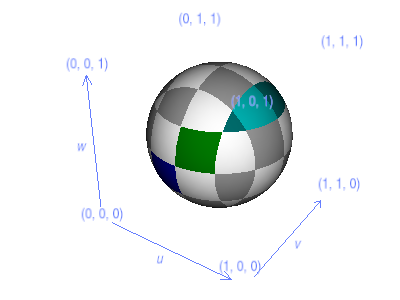

This is true no matter what shape we carve out of the cube:

In addition to the usual u and v texture dimensions, a

3-D texture also has w. In order to apply a 3-D texture to

geometry, you will therefore need to have 3-D texture coordinates

(u, v, w) on your geometry, instead of just the ordinary (u,

v).

There are several ways to get 3-D texture coordinates on a model. One

way is to assign appropriate 3-D texture coordinates to each

vertex when you create the model, the same way you might assign 2-D

texture coordinates. This requires that your modeling package (and

its Panda converter) support 3-D texture coordinates; however, at the

time of this writing, none of the existing Panda converters currently

do support 3-D texture coordinates.

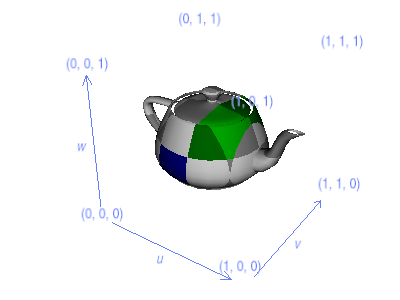

More commonly, 3-D texture coordinates are assigned to a model

automatically with one of the TexGen modes,

especially MWorldPosition. For example, to

assign 3-D texture coordinates to the teapot, you might do something

like this:

teapot = loader.loadModel('teapot.egg')

teapot.setTexGen(TextureStage.getDefault(), TexGenAttrib.MWorldPosition)

teapot.setTexProjector(TextureStage.getDefault(), render, teapot)

teapot.setTexPos(TextureStage.getDefault(), 0.44, 0.5, 0.2)

teapot.setTexScale(TextureStage.getDefault(), 0.2)

|

The above assigns 3-D texture coordinates to the teapot based on the

(x, y, z) positions of its vertices, which is a common way to assign

3-D texture coordinates. The setTexPos() and

setTexScale() calls in the above are particular to the

teapot model; these numbers are chosen to scale the texture so that

its unit cube covers the teapot.

Storing 3-D texture maps on disk is a bit of a problem, since most

image formats only support 2-D images. By convention, then, Panda3D

will store a 3-D texture image by slicing it into horizontal

cross-sections and writing each slice as a separate 2-D image. When

you load a 3-D texture, you specify a series of 2-D images which

Panda3D will load and stack up like pancakes to make the full 3-D

image.

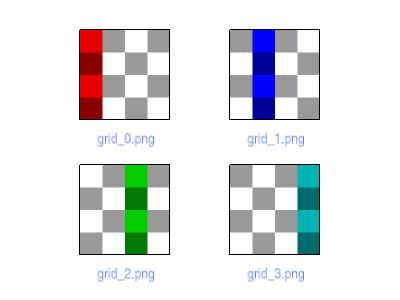

The above 3-D texture image, for instance, is stored as four separate

image files:

Note that, although the image is stored as four separate images on

disk, internally Panda3D stores it as a single, three-dimensional

image, with height, width, and depth.

The Panda3D convention for naming the slices of a 3-D texture is

fairly rigid. Each slice must be numbered, and all of the filenames

must be the same except for the number; and the first (bottom) slice

must be numbered 0. If you have followed this convention, then you

can load a 3-D texture with a call like this:

tex = loader.load3DTexture("grid_#.png")

|

The hash sign ("#") in the filename passed to

loader.load3DTexture() will be filled in with the

sequence number of each slice, so the above loads files named

"grid_0.png", "grid_1.png", "grid_2.png", and so on. If you prefer to

pad the slice number with zeros to a certain number of digits, repeat

the hash sign; for instance, loading "grid_###.png" would look for

files named "grid_000.png", "grid_001.png", and so on. Note that you

don't have to use multiple hash marks to count higher than 9. You can

count as high as you like even with only one hash mark; it just won't pad

the numbers with zeros.

Remember that you must usually choose a power of two for the size of your texture images. This extends to the w size, too: for most graphics cards, the number of slices of your texture should be a power of two. Unlike the ordinary (u, v) dimensions, Panda3D won't automatically rescale your 3-D texture if it has a non-power-of-two size in the w dimension, so it is important that you choose the size correctly yourself.

Applications for 3-D textures

3-D textures are often used in scientific and medical imagery

applications, but they are used only rarely in 3-D game programs. One

reason for this is the amount of memory they require; since a 3-D

texture requires storing (u × v × w) texels, a large 3-D

texture can easily consume a substantial fraction of your available

texture memory.

But probably the bigger reason that 3-D textures are rarely used in

games is that the texture images in games are typically hand-painted,

and it is difficult for an artist to paint a 3-D texture. It is

usually much easier just to paint the surface of an object.

So when 3-D textures are used at all, they are often generated

procedurally. One classic example of a procedural 3-D texture is wood

grain; it is fairly easy to define a convincing woodgrain texture

procedurally. For instance, click here to view

a Panda3D program that generates a woodgrain texture and stores it as

a series of files named woodgrain_0.png, woodgrain_1.png, and so on.

The following code applies this woodgrain texture to the teapot, to

make a teapot that looks like it was carved from a single block of

wood:

teapot = loader.loadModel('teapot.egg')

teapot.setTexGen(TextureStage.getDefault(), TexGenAttrib.MWorldPosition)

teapot.setTexProjector(TextureStage.getDefault(), render, teapot)

teapot.setTexPos(TextureStage.getDefault(), 0.44, 0.5, 0.2)

teapot.setTexScale(TextureStage.getDefault(), 0.2)

tex = loader.load3DTexture('woodgrain_#.png')

teapot.setTexture(tex)

|

However, even procedurally-generated 3-D textures like this are used

only occasionally. If the algorithm to generate your texture is not too

complex, it may make more sense to program a pixel shader

to generate the texture implicitly, as your models are rendered.

Still, even if it is used only occasionally, the 3-D texture remains a

powerful rendering technique to keep in your back pocket.

|